THE REAL BOOK OF REVELATION

Reframing Revelation: Rediscovering the Lost Apocalypse of John

A growing body of historical, theological, and digital scholarship is challenging long-held assumptions about the origins of the Book of Revelation. Once viewed as a static endpoint of apocalyptic tradition, Revelation is now being reconsidered as a fluid, contested, and possibly misrepresented text, one that may have originally expressed a radically different vision of Christian eschatology.

A Forgotten Revelation Resurfaces

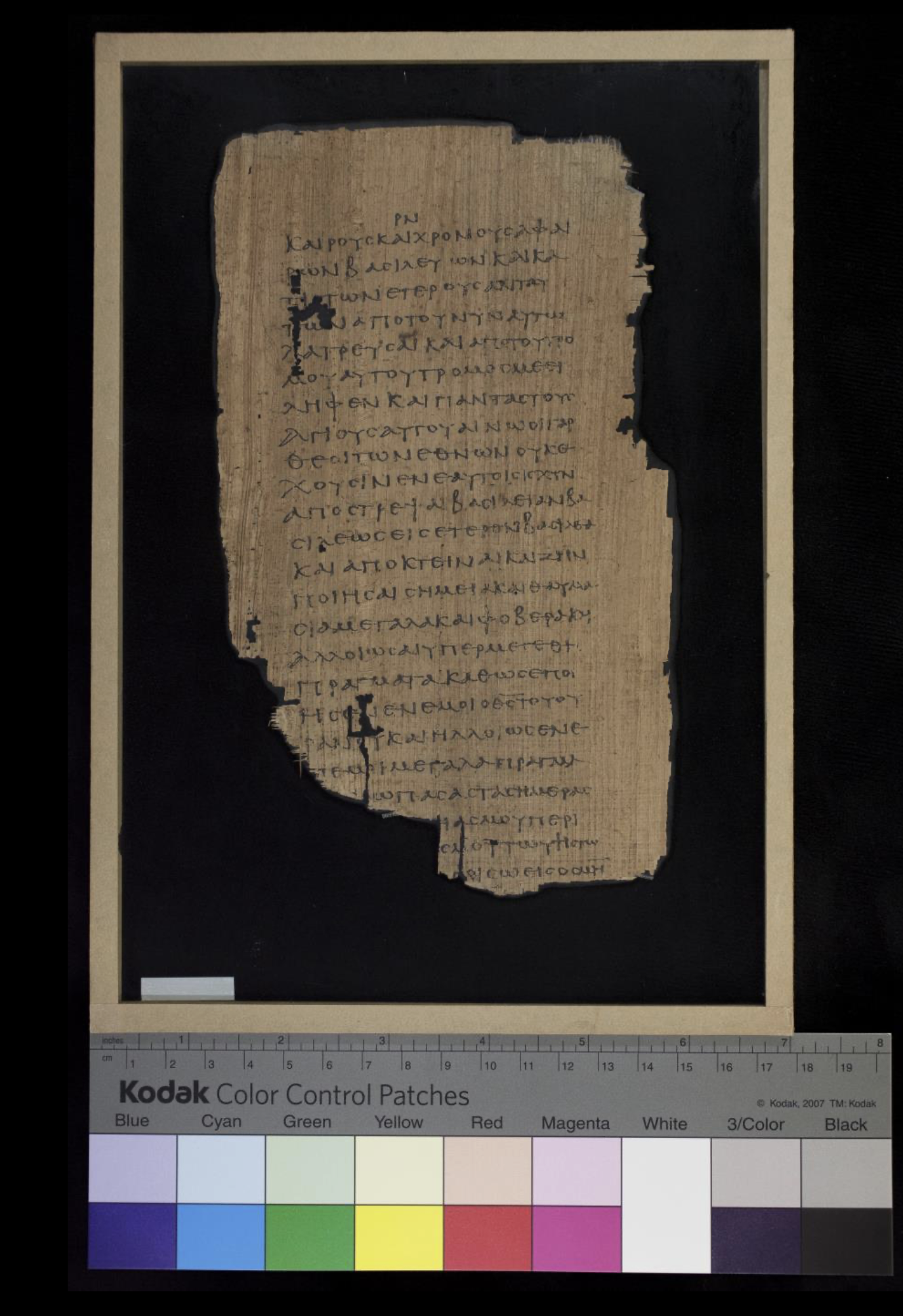

In a recent interdisciplinary breakthrough, scholars have used advanced machine learning—specifically the Ithaca neural network developed by DeepMind—to assist in the reconstruction and attribution of four early textual fragments. These fragments, written in Koine Greek and Occitan, span from the Roman catacombs to postwar Bosnia, southern France, Gaza City, and possibly subterranean Cappadocia. Carbon dating, paleographic analysis, and AI-assisted restoration suggest that they stem from an earlier, alternative version of Revelation, written down by Polycarp and his house around 155 CE and attributed directly to John, the disciple of Jesus.

Unlike the canonical version, long associated with apocalyptic violence and divine retribution, this reconstructed text emphasizes inner transformation, nonviolence, and the endurance of love in the face of empire. As lead researcher Dr. T. Sommerfeldt puts it:

“This is not the Revelation of beasts and blood, but of vision and memory, an eschatology of hope rather than destruction.”

Echoes from Antiquity: Was the Original Revelation Suppressed?

This discovery aligns strikingly with ancient doubts recorded by early Church historians. In the fourth century, Eusebius of Caesarea classified Revelation as one of the antilegomena, disputed books, while the third-century bishop Dionysius of Alexandria famously wrote:

“Some before us have set aside the Apocalypse... and have pronounced it the work of some heretic... I suppose that it was not written by John the Apostle, but by another John.” (Ecclesiastical History VII.25)

Dionysius highlighted the book’s crude Greek and theological dissonance with the Gospel of John. These early critiques have prompted modern scholars to ask:

Did the version of Revelation revered by Polycarp, Irenaeus, and other early fathers differ from the one canonized centuries later?

Recent scholarship increasingly supports the notion that multiple apocalyptic texts bearing John’s name circulated in the second century, and that the surviving version may have been standardized, or even substituted, during later phases of canon formation.

Canonical Politics: How the Revelation We Know Was Preserved

Despite its disputed origins, the Revelation we know was ultimately included in the New Testament canon through a complex mix of ecclesiastical politics, regional preferences, and imperial centralization:

In the West, figures like Tertullian, Jerome, and Victorinus embraced the text’s millenarian tone and cosmic judgment.

thanasius of Alexandria listed it in his 367 CE canon, which heavily influenced the Councils of Hippo (393) and Carthage (397).

Under Constantine, theological diversity gave way to unification, and Revelation—despite ongoing resistance in the East—was absorbed into the canon for the sake of ecclesial coherence.

A New Chapter in Biblical History?

If authenticated, this reconstructed “lost Revelation” could significantly reshape theological understandings of early Christianity. It suggests a Johannine theology rooted in mystical memory and resistance through love, rather than apocalyptic determinism, a strand of early Christian thought long overshadowed by Pauline eschatology and imperial orthodoxy.

More than a digital curiosity, this AI-assisted project underscores a broader truth: the Bible is not a fixed artifact, but a living archive, one shaped by memory, omission, and the ever-evolving tools we use to interpret its fragments.

Validation is ongoing. But if confirmed, this rediscovered Apocalypse of John may yet reopen the canon—not by changing its contents, but by transforming how we read it.

Contact Us

We are willing to answer all of your questions!